BHS Tutorial

BHS Tutorial

Providing individualized, content-based support to enhance the academic performance of students with mild learning difficulties.

After initial funding from the BHS Innovation Fund, BHS Tutorial is fully integrated into the Brookline High School curriculum.

By Federal and State law, school districts are required to provide children with special educational needs a “free appropriate public education.” Due to advances in medical technology, an increase in the number of children living in poverty, and the requirement to educate children in their local schools rather than in outside institutions, more children with special needs are entering and being served in the public schools. As a result, special education (SPED) expenditures nationally and across Massachusetts have risen dramatically in the last decade. Exemplifying this, Brookline’s expenditures on SPED programs have increased about 70% since fiscal year 2001 — the cost of SPED services has grown by close to 30% per year. As a result, SPED now accounts for more than 25% of Brookline’s overall school budget with approximately 20% of enrolled students receiving services (the statewide average in Massachusetts in approximately 17% of enrolled students).

Given constraints on state and local budgets, these mandated increases in SPED spending mean that school districts are increasingly forced to cut other services (e.g., honors programs, arts and music curriculum, athletics, and early childhood programs) in order to sustain balanced budgets.

This exceptional growth in special education expenditures is a national issue. The Innovation Fund introduced three programs to address this issue directly: Tutorial (for students in grades 10–12), Freshman Tutorial, and Enhanced Tutorial. These programs have not only reduced the cost of special education within Brookline High School by approximately $240,000, but they have also met the needs of students with less serious yet notable learning issues within the mainstream of the school community and without having to provide them with costly SPED services.

The Tutorial Program represents a radical change in the structure and organization of the school. With increasing interest in educating students with disabilities in inclusive settings, and with federal requirements mandating that all students achieve high academic standards, BHS identified an opportunity to restructure its approach to special education.

The BHS Tutorial Program began as a pilot program in 2002 involving eight teachers and 40 students to test the theory that individualized academic support would enhance the academic performance of students challenged by mild learning difficulties with the same success as a more expensive special education alternative.

BHS Tutorial now serves students with any of the following academic profiles:

- Students needing assistance to meet the course expectations of an Honors or Advanced Placement class;

- Students with organizational difficulties;

- Students needing additional review of course content to gain mastery of material;

- Students operating “under the radar” who could benefit from individual support.

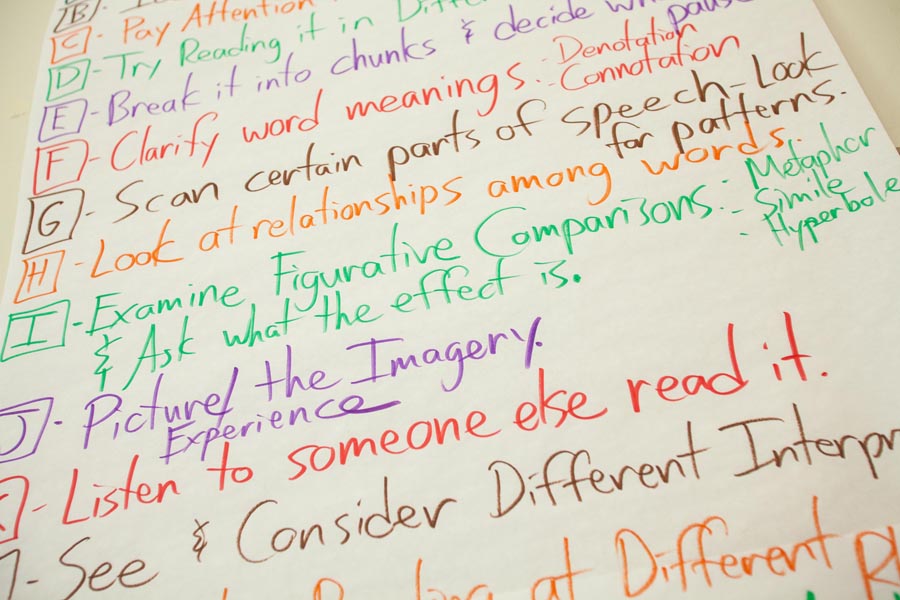

In collaboration with their Tutorial teachers, students identify specific focus areas for improving academic performance and receive individual content-based tutoring. Class time is divided between personalized consultation in content areas and independent practice (where the student implements recommended strategies).

A two-year evaluation study was completed in 2004, led by Thomas Hehir of the Harvard Graduate School of Education. It concluded that the program was equally as effective as special education services for students with mild learning disabilities with regard to standardized test scores, and slightly more effective in improving course grades. The report praised the Innovation Fund’s Tutorial Program as an innovative and impressive alternative to traditional special education programs for these students.

In 2006, Watertown High School launched its own Tutorial Program based on the BHS Innovation Fund model. Lexington High School has also reviewed our program and is examining ways to incorporate many of the program elements into their curriculum. Detailing the Tutorial’s support of special needs students, a professional paper authored by BHS Headmaster Dr. Robert Weintraub and Fund Co-Chair Julie Joyal Mowschenson entitled “Beyond Special Education: A New Vision of Academic Support in the 21st Century” will be published in the winter of 2009 by the Phi Delta Kappan, the country’s leading educational journal.