Students in EPIC create businesses to explore their passions. Seniors Talia Thompson and Cece Wager made an acai business to serve their community.

Throughout the years, students have built homemade skis, established rugby programs for middle schoolers and learned how to pickpocket, all thanks to the guidance of one class.

Experiential Project Based Capstone (EPIC) is a senior English class that allows students to design their own projects to complete a personal goal. The class is currently taught by English teacher Ben Berman. The projects can be whatever the student wants, as long as it can be completed during an allocated ten weeks during the spring semester.

Throughout the year, EPIC students focus on different topics such as decision making skills, what brings them happiness and more. Questions like “Who am I now?” and “Who do I want to be?” help students decide on what they want to pursue. After researching, students come up with a capstone project proposal which they pitch to Berman. They then spend the second semester working towards that goal.

Because it’s an English class, the students generate many written reflections, detailing their progress and goals. Berman said that EPIC pushes students to learn because they want to achieve meaningful work and not because they just want to get a good grade.

“A lot of school is really teacher-directed, in terms of we determine what you need to learn, why it’s important and how we are going to measure your success. Students don’t have tons of autonomy to figure out what they’re interested in and to let that drive what they study,” Berman said.

Senior Cece Wager decided to take EPIC because it was unlike the other normal classes at the high school. She felt that it was more open and it helped students build their skills as a person. The specific skill that Wager was working on was her communication.

“COVID hit right during my freshman year, which was really hard. Everything was online and nobody talked to each other face-to-face. I struggled with talking to people in-person, and I got a lot of anxiety. So I really want to work on that before college because there’s a lot of stuff that you need to do in person,” Wager said.

To achieve her goal, Wager partnered up with senior Talia Thompson, her close friend and soccer teammate. The two had traveled to California for soccer and found their inspiration. Together they decided to make an acai business, influenced by the many acai places there, for their capstone project. Wager said she is happy with their project.

“I love being able to share something that I love with the community, with BHS, with the students, with the faculty, with the kids that are running around in the park and coming up to us and asking us questions. It’s so sweet,” Wager said.

Wager said that while starting the business has been super fun, it was also challenging. They had to find and source the ingredients, calculate the price per bowl and then actually make and sell them. Wager said that they reached out to people in and around the high school for advice. Through instagram direct messaging, phone calls, or simply showing up, Wager and Thompson talked to other acai businesses, teachers and even gas station managers.

Wager and Thompson weren’t the only students to create a product to sell this year. Senior Joel Gutierrez attempted to create a container to store and lock up one’s water bottle while they go on a run. The idea stemmed from a conversation with his father.

“One day my dad came home and he was frustrated because he had to carry his water bottle with him and he didn’t really like those water bottle straps that you can use to carry it in your hand, so I thought that I would approach it from a different angle,” Gutierrez said.

While working through his project, Gutierrez realized that actually designing individual products and trying to produce them wasn’t what he wanted to do. If he wanted to start a company he would want to create it around a bigger idea, not just one product, as a broader vision provided him with more motivation. While Gutierrez didn’t finish his initial idea, he did achieve something else: an epiphany.

“I wanted to figure out how I can make my life more exciting. I had this conversation with my mom about the fear of missing out, and I came to the conclusion that I need to step up and do things if I want to get rid of that fear,” Gutierrez said.

Gutierrez realized that to make your life exciting you need to take risks and participate in unique experiences. He took a risk and while things didn’t work out exactly how he hoped, he was still content with what he had achieved.

Not all EPIC students were focusing on making things more exciting; one was actually looking to make her life less exciting.

Senior Nemiera Lal’s capstone project was centered around mental health. She wanted to focus on her peace of mind in the midst of her senior year and the stress of college. EPIC allowed her to design a project that prioritized reflection on her emotions and furthered her communication skills.

“Through EPIC I decided to try out different small things: napping was the biggest one, and journaling every week. One of the biggest things I did was say no to friends, which is something new for me because every time someone asked me to hang out I would just immediately say ‘yes,’” Lal said. “Through EPIC, I started consciously making the decisions for myself and never letting other people decide where I am and where I go. It’s me who decides what I do.”

Initially, Lal had a slightly different idea. She was planning on spending more time with others as a way to deal with her friends leaving after graduation. But as Lal spent more time with others, the more she realized that it was something that she did all the time, even before EPIC. When she took time for herself, it felt as though she was wasting time.

“One of my activities was just laying down and listening to music and that was such a hard feeling for me. Even though it was relaxing, I just wanted to get up again and again. I was fighting the urge to do something,” Lal said.

But Lal persevered and said that now, she feels a deeper connection with her family and is able to have more focused conversations with her friends, all because of EPIC.

Berman said that is one of the best and the most challenging thing about EPIC. It’s more difficult to complete a task when it is so ambiguous, but the result is more rewarding.

“You get to work with students as people. Instead of me telling them what they need to learn, I’m constantly learning about their interests and encouraging them to take personal risks and helping them understand through the act of reflection and what it means to live a meaningful life,” Berman said.

Flannery Poon, Staff Writer|May 15, 2023

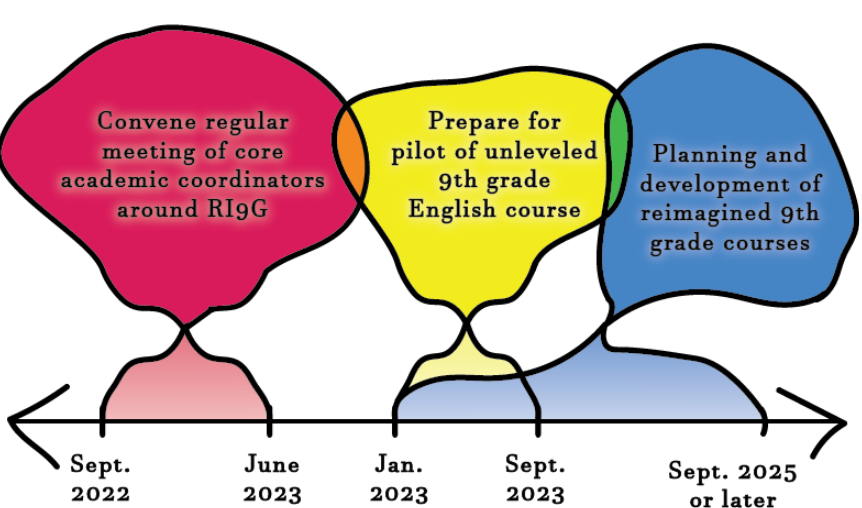

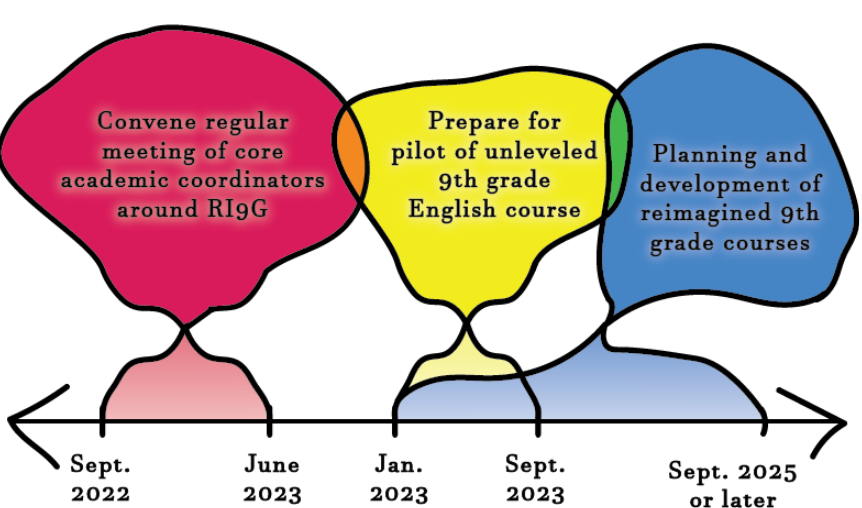

In a Brookline School Committee meeting on Jan. 19, Head of School Anthony Meyer presented the School Improvement Plan goal of Re-imagining Ninth Grade (RI9G). To achieve the different action items, the timeline includes regular meetings and course pilots.

Brookline moves to delevel 9th grade

Hard choices within high school

Connor Quigley and Anisa Sharma

GRAPHIC BY EZRA KLEINBAUM

March 24, 2023

Anew structure of 9th grade leveling could be just around the corner. For many years, curriculum coordinators and program coordinators, special education administrators and teachers have wrestled with the goals and consequences of deleveling 9th grade.

In a Brookline School Committee (BSC) meeting on Jan. 19, 2023, Head of School Anthony Meyer presented the School Improvement Plan (SIP) goal of Reimagining 9th Grade. To fulfill the SIP goal, the set timeline includes regular meetings and course pilots. Coordinators are bringing this mandate to their respective departments to discuss implementation.

Gabe McCormick, Senior Director of Teaching and Learning for PSB, said the effort to reimagine 9th grade was initially spearheaded by Lesley Ryan Miller, former Deputy Superintendent of Teaching & Learning, and other district administrators.

In Fall 2019, the social studies department introduced the high school’s first required unleveled course in a core subject for 9th graders, World History I: Identity, Status, and Power (WHISP). The class centers around collaborative, project-based learning.

Following the introduction of WHISP, McCormick said the effort was interrupted by COVID-19. He said after the district came out of emergency mode, the effort to delevel has been thought about more strategically and systematically.

In the meeting on Jan. 19, Meyer said administrators were concerned that students tend to stay at the level they are recommended for in 8th grade. Research by the social studies department prior to the development of WHISP confirmed that students in college preparatory 9th grade social studies tended to continue with that level.

The English department will launch a pilot, unleveled 9th grade English course, Responding to Literature/Humanities, in Fall 2023. Focusing on forming a community within the classroom and personalizing each student’s English learning experience, the course will be organized to overlap with WHISP.

Rising freshmen taking courses in the English Department for the 2023-24 school year have been recommended for the two pre-existing Responding to Literature and Responding to Literature Honors courses and the unleveled pilot Responding to Literature/Humanities for 9th grade English. Of the 541 8th graders recommended for a 9th grade English course in the upcoming school year, teachers recommended 20 percent of them for the pilot course.

New pilot courses for world language and math are planned to be introduced in Fall 2024.

Social Studies Curriculum Coordinator Gary Shiffman said he sees leveling exacerbate a culture of relentless academic pressure from a young age. In freshman and sophomore year classes, Shiffman said there should be more of a focus on guiding and supporting students.

“What kind of college you go to is not what we want to talk about with the freshmen. In the lower grades, we really need to think carefully about what impressions we’re giving students of themselves and what we think of them,” Shiffman said. “We want to communicate to you as a student that we want you to work as hard as you can, and let’s find out what that is.”

Rethinking courses will influence the experiences of nearly every 9th grader. Special Education Coordinator of Therapeutic Programs Jedidiah Miller said he anticipates both discomfort and negative responses from the broader community.

“Anywhere, anytime you’re making change, especially when it’s big and it impacts a lot of different people, there are going to be people that are uncomfortable with it. It comes from many different sources, it comes from people [who think] that the way we’ve always done it is the easy thing, the low energy state,” Miller said. “You have to overcome some of that stagnation or the fear of change and have a really clear sense of urgency around it. There’s always going to be some backlash to that too.”

Share this:

Click to print (Opens in new window)Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

Deleveling for equity

Miller said since students in special education participate in general education courses based on their Individualized Education Programs (IEPs), it is vital for the special education department to be involved in the discussion to delevel courses.

“All special education students are general education students. When we talk about changing and modifying the way that we approach anything through general education, we want to make sure that our students with disabilities are being supported and served the best way so they can continue to access and, in fact, even increase their access to general education,” Miller said. “We want to make sure that [in] any efforts to make changes, we minimize the impact and see it as an opportunity to make gains for our students in terms of access.”

Former Director of Special Education Aida Ramos was one of several representatives from the special education department in the deleveling conversation.

“I was glad to be invited to be part of the conversation and be part of the group, because then the voices of SWD are also there, and the benefits of deleveling and accessibility to other classes and being able to participate more with typical peers is a focus of the conversation too,” Ramos said.

Miller said the deleveling of 9th grade history through WHISP has allowed special education students access to greater curriculum and content, so he looks forward to the idea of more classes becoming heterogeneous.

However, according to Miller, for subject areas like science, world language and math, students need to solidify certain areas of knowledge to progress academically, making deleveling more complicated.

“In science and word language [and] math, there are sequences to the curriculum. So there are certain foundational content skills that you need to work on and shore up to be able to access the next phase because, like a building, the foundation needs to be solid enough to move up to the next thing,” Miller said.

English and African American and Latino Scholars Program (AALSP) teacher Emma Siver said students of color are often negatively impacted by the leveling structure because of systemic inequities.

“There’s a lack of family [outreach] to students of color when it comes to understanding the leveling process and the parent connection there. That can be for various reasons of home circumstances,” Siver said. “Also, if you primarily walk into an honors classroom right now, you’re more likely to see less students of color – that can come from lack of seeing themselves in the space. More often than not, if you don’t have someone that can share or connect with you, you’re less likely to want to initiate or engage in that type of dynamic.”

Share this:

Click to print (Opens in new window)Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

Deleveling across departments

SCIENCE

Science Curriculum Coordinator Ed Wiser said the science department is still in the preliminary stages of considering what an unleveled 9th grade physics class would look like. He said the science department has been at the forefront of rethinking what high school science education can look like across the nation.

According to Wiser, the approach of taking physics during freshman year instead of later grades has allowed for a more accessible, engaging curriculum and increased the heterogeneity of higher-level science courses.

McCormick said the physics team, funded by the Innovation Fund, has done extensive work to align the curriculums of the 9th grade college preparatory and honors levels of physics. Before this alignment, McCormick said the honors physics class was structured differently in terms of units and content.

“Now, [the honors and college prep courses] do [have] different complexities, but the courses are going through the same content at the same time. And so part of my hope is that because they’ve done that work of aligning the curriculum of the classes, now we can think about how to put a wider variety of students in the same room,” McCormick said.

WORLD LANGUAGE

Ninth graders can choose between Chinese, French, Japanese, Latin and Spanish for world language. Depending on the language, there are between one and four levels for 9th grade.

World Language Curriculum Coordinator Rachel Eio said although the world language department plans to reimagine the structure of levels by welcoming mixed-grade courses, removing all leveling in 9th grade is unrealistic because of the wide range of experiences with languages for incoming students.

“If we think about deleveling, what does it mean to put kids all together in a room, some who have intermediate level proficiency skills? We have students who can do really sophisticated things by the time they’re getting to 9th grade, particularly in Spanish and French, and then we have kids who have never studied Spanish at all,” Eio said. “You can’t put them in the same room; it makes no sense whatsoever. It’s not good for the students, it’s not good for the teachers.”

When students transition from 8th grade in the PSB, world language switches from a special subject to a core subject area, and the high school has a two-year language graduation requirement. Eio said this structure presents scheduling challenges in the middle schools, as students with special education needs are often taken out of language classes and enter the high school with limited language experience.

“The reality is that we have a broken system when we think about the ways in which kids are getting pulled from world language in K-8,” Eio said. “It’s creating really inequitable classes. Those are challenging classes, and kids can’t progress in the language that they’re studying because they’re starting so late.”

Eio said the department is in the beginning stages of developing a new program and will potentially launch a 9th grade pilot in Fall 2024. Based on levels of proficiency, the department hopes to reduce the number of levels across grades and introduce courses that will likely be thematic and include embedded honors options.

McCormick said that since students enter 9th grade with a multitude of language abilities, the department would have to extensively rework many courses to design an unleveled 9th grade course.

“We basically have to change every course in world language. That is a much bigger endeavor [than for English and science]. We’re not giving the department a specific timeline, but we’re sort of making sure everybody’s on the same train,” McCormick said.

MATH

When students enter the high school as freshmen, Math Department Chair Josh Paris said leveling in classes imposes labels that often stick with them throughout their four years. There are currently three levels of math for 9th graders: college preparatory, honors and advanced.

“As students come in from the middle schools, a lot of the message that we give to them is that high school is a chance to reinvent yourself, to reimagine who you are as students. And yet, before they even get here, we label them, which impacts their identities as students and as mathematicians. We make it so much more difficult for students to reimagine who they are,” Paris said.

Paris said the racial distribution across levels of 9th grade math courses has also motivated the movement to reconsider leveling.

In the 2020-21 school year, course enrollment data shows that of Black freshmen enrolled in a Geometry class, 47 percent were enrolled in college preparatory Geometry, 42 percent in Geometry Honors and 11 percent in Geometry Advanced. Of Asian freshmen in a Geometry class, nine percent were enrolled in college preparatory Geometry, 42 percent in Geometry Honors and 48 percent in Geometry Advanced.

“If you look at the racial breakdowns of our levels, students of color are underrepresented in both honors and advanced,” Paris said. “We have the Calculus Project, which has done a lot of work at the high school to combat that and to improve those numbers and with a lot of success, but that opportunity gap still remains. Our leveling structure creates racialized outcomes.”

According to Paris, the math department has worked on constructing new 9th grade programming for around six years. He said they initiated a pilot program merging levels during the 2017-18 and 2018-19 school years and hoped to have developed a new program along with the opening of 22 Tappan, until COVID-19 forced a shift in focus.

“We took a section of college prep, a section of honors, a section of advanced and remixed them and put them in more heterogeneously grouped classes. We really thought carefully about what a unit would look like taught to a heterogeneous population,” Paris said. “We learned a lot from that on how the students’ experiences differ in the various units and the work we need to do to create a program that serves all students well in order to reflect their differences.”

Paris said the math department is currently looking into embedded honors and similar models that could allow students to elect for an honors credit in a mixed-level classroom. However, he said the current structure of the 9th grade math program with three levels makes condensing levels more complicated.

“We don’t know what model we’re going to have, but we need to provide opportunities in 9th grade with whatever model we choose. We need to prepare students to be able to access honors and advanced level work beyond 9th grade. So part of the work we do in 9th grade will be to provide students access to get to that level of work,” Paris said.

Before a 9th grade pilot of alternative leveling, Paris said the department plans to conduct student polls to better understand 9th graders’ experiences in their current math classes.

“We definitely plan to involve all stakeholders in thinking through why we’re doing this and what it would look like,” Paris said. “I’ll have a group of teachers that will teach 9th grade that will be taking the lead, but we want to make sure that we involve parents in the process and students because it’s the students’ experiences that we are hoping to improve, and we want to hear from students about their experiences.”

Freshman Alya Barsky-Elnour said the speed and structure of her college preparatory Geometry class have allowed her to gain confidence in her mathematical abilities, and she now is considering moving to honors for sophomore year math.

“Being in this math class this year has really helped me feel more secure,” Barsky-Elnour said. “They’re recommending me for honors, so I might give that a go.”

Barsky-Elnour said students in college preparatory Geometry may be constricted by a negative mindset.

“For a lot of kids, and a lot of them are kids of color, they feel like they can’t move up. I think that I’m lucky to not be one of those people,” Barsky-Elnour, who is Black, said. “I think some kids are too comfortable where they are. They think they can’t do better. A lot of students don’t believe in their brain and don’t think they’re smart enough.”

Both Barsky-Elnour and freshman Jackson Musto, who is taking Advanced Geometry, said they enjoy the dynamics of their math courses this year, especially in contrast with their unleveled 8th grade courses.

“It’s a really welcoming environment, way more than my 8th grade year was. They are really welcoming when you’re wrong,” Barsky-Elnour said. “I think it’s a really nice and more calm environment in which I feel a lot more comfortable raising my hand, and I’m not ashamed of being wrong.”

If an unleveled Geometry option had been available, Barsky-Elnour said she likely still would have elected to take the college preparatory Geometry course.

“I don’t think I would have jumped at that opportunity just because that’s how it was in middle school; it was the same three people who were always the ones answering. I think that’s what contributed to my thinking that I wasn’t in the place that was for me,” Barsky-Elnour said.

One of the challenges in creating a new math program is that 9th grade lays the foundation for future levels, eventually leading to more advanced math courses offered to juniors and seniors. Paris said he aims to have more students enroll in math courses of higher levels as upperclassmen.

“If you group all students together, and we don’t know what the plan is going to be, [but] there’s a danger we’ll teach the kids in the middle. But if you do that, then the students with stronger math backgrounds don’t get their academic needs met, nor do the students who have more math and academic challenges,” Paris said. “The goal is to make sure that all students, wherever they are mathematically, are challenged and supported. I think that’ll be the basis of the way we design the courses.”

The advanced track of math culminates with AP BC Calculus. The course covers the college courses of Calculus I and Calculus II at a college-level pace. Senior Amit Piryatinsky, who is in AP BC Calculus, said he has enjoyed advanced math and appreciates how it has prepared him for his future.

“[AP BC Calculus] is a challenging course, but I enjoy learning math and that is why I am in advanced,” Piryatinsky said. “Diving deep into math and into what, in my opinion, is one of the most interesting parts of math, is enabled by not only the speed and rigor of the course, but also the environment.”

Piryatinsky pointed out that a majority of people who enroll in advanced math in 9th grade engaged in supplemental math education in middle school. This can be challenging for students in advanced math who have not had access to auxiliary math education.

Musto said he would not have chosen to take an unleveled Geometry option because of the slower pace it would likely assume compared to the advanced level.

“I think what makes Advanced [Geometry] a good class is that it moves at a very quick pace that the people who are supposed to be taking [the class] can keep up with,” Musto said.

Piryatinsky said deleveling may limit advanced track students from reaching their full potential.

“I think the idea of deleveling is a good one, but I fear that it could lead to this idea of, instead of nobody left behind it ends up being nobody running ahead, that [deleveling] kind of restricts people from excelling,” Piryatinsky said.

HISTORY

Shiffman said some class blocks of WHISP do not have a truly varied selection of students, especially in regard to students who require co-teaching support as part of their IEPs.

“Co-teaching is a limited resource, so what we’ve ended up doing is forcing a whole bunch of kids who have learning disabilities into particular sections,” Shiffman said. “There are parts of the scheduling process that exacerbate that… [some blocks] aren’t heterogeneous: they’re homogeneous with a lot of kids with high needs, and that’s a problem.”

Shiffman said prior to the creation of WHISP, the distinction of taking an honors class was not meaningful, with close to 70 percent of freshmen taking honors social studies.

Shiffman said he remembers observing a 9th grade college preparatory social studies class in which two students were discussing a series of documents. He said he saw their enthusiasm and intelligence in the small group but that during the whole class discussion, their demeanor was “cavalier.”

“What’s going on is [the students are] comfortable here. I would like them to be a little less comfortable and rise up to the expectations they deserve to have for themselves,” Shiffman said. “I just started thinking if these kids were in an honors class, they would do fine. And I just started to think, why exactly are they in this level, not at that level?”

Share this:

Click to print (Opens in new window)Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

Concerns over recommendations

In data from the teacher recommendations for the incoming Class of 2027, six percent of Black 8th graders who will take a course in the math department were recommended for Advanced Geometry. Thirty percent were recommended for Geometry Honors and 64 percent were recommended for the college preparatory Geometry course.

In the BSC meeting on Jan. 19, Meyer said 8th grade teachers’ recommendations are a concerning factor that influenced the decision to reimagine 9th grade across the board.

“Teachers know students incredibly well, and we count on them to make good recommendations. We believe they do so in an incredibly thoughtful and well-intentioned way,” Meyer said. “And we have data that is concerning and has been concerning and thus the idea of rethinking our 9th grade courses, where we’re not asking students and teachers to decide, ‘Are you an honors student?’ in the middle of 8th grade.”

Even with teachers trying their best to recommend students, Siver said a systemic lack of communication plays a role in racial gaps in recommendations for 9th grade courses.

“The end goal of anyone’s education is to have all these set foundational skills come to fruition. If you don’t lay down the foundation or a clear map of how that can come to be, then people get lost along the way. It ties into this idea of perhaps a greater sense of organization being a necessity amongst many tiers, not here in Brookline, but across many districts,” Siver said.

Paris said shifting students’ first recommendations from 8th grade teachers to 9th grade teachers will result in more consistent course recommendations.

“I think the 8th grade teachers and counselors do a really good job of recommending students. It’s a hard task, and I think they take it very seriously and I think they’re very informed about our high school program. The issue is that there are eight different elementary schools and so, just with that fact alone, you’re going to get disparities in the way that recommendations are made,” Paris said.

Barsky-Elnour said the college preparatory level for 9th grade math was the right choice for her.

“I talked to my main class math teacher, and he said that I should do honors if I was ready to put in the work and to spend a lot of time on math, but he had recommended me for standard at the time,” Barsky-Elnour said. “I didn’t really believe that I had the means to be in an honors class. I don’t think I was quite ready to accept that I would have to put all that work, because I didn’t in my 8th grade year.”

When 8th grade teachers recommended students for 9th grade English courses for the 2022-23 school year, 63 percent of students identifying as Black or African American (17 students) were recommended for the college preparatory English course, according to a Public Schools of Brookline (PSB) Data Report, as opposed to the honors option. Twenty-four percent of white students (68 students), 27 percent of Asian students (21 students), 52 percent of Hispanic students (32 students) and 29 percent Multi-Race Non-Hispanic students (14 students) were recommended for the college-preparatory English course.

While parents can override recommendations from teachers, McCormick said 9th grade students usually stick with their 8th grade teacher recommendations.

This trend of students staying in the level they were recommended for in 8th grade continues throughout their years in high school. According to data from PSB enrollment and teacher recommendations for the Class of 2025, two percent of students recommended for a course in the social studies department overrode their recommendations.

“If you’re like a really empowered parent, and you’re like, ‘I know [how] that school works, my kid can take honors,’ you’re gonna go do that,” McCormick said. “If you’re less empowered, maybe you didn’t have a good school experience as a student, you may not question it. If you’re just busy and you just don’t have the time, you have maybe lots of kids, you work multiple jobs or your first language is not English, all of that makes it harder.”

According to Barsky-Elnour, the level of math that students are prepared to do can be limited by their middle school experience with math.

“I think [there is] a systemic level issue that builds in middle school, that teachers aren’t pushing kids of color enough as they go. So when they get to their 8th grade year, maybe they don’t have the skills for honors,” Barsky-Elnour said.

Share this:

Click to print (Opens in new window)Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

Learning from WHISP

While WHISP is the sole social studies option for all 9th graders, 10th and 11th grade both offer college preparatory and honors level classes, as well as “earned honors” options in Global Studies (10th grade) and American Studies (11th grade), courses where students are in a mixed classroom and some elect to do specific work to earn an honors credit.

Before the introduction of Global Studies in Fall 2021, the typical options within the social studies department for 10th graders were World History at the honors and college preparatory levels.

Shiffman said he wishes the 11th grade earned honors American Studies classes were even more heterogeneous in terms of race, ability and gender. He said a truly heterogeneous class creates a collaborative learning environment where students with diverse backgrounds and experiences can learn from each other.

“I think it’s hard to maintain the culture of pushing in a class where too many kids struggle too much of the time. I love being able to devote attention to kids in that context,” Shiffman said.

Shiffman said he has seen WHISP offer an opportunity in social studies for students in a large public high school to come together without an immediate separation.

“Do we have to separate you the second you walk in the door and say, ‘We’re going to discuss human society – you guys go over there and you guys go over there?’ It just began to seem so antithetical to the enterprise,” Shiffman said.

WHISP was first introduced for the Class of 2023 in Fall 2019. Based on teacher recommendation data for the Class of 2020 through the Class of 2025 (using a 95 percent confidence interval), the percentage of students recommended for World History Honors did not increase for the race categories of African American, Asian, Hispanic, White and Multi-Race Non-Hispanic after WHISP was introduced (of all tenth graders recommended for either World History courses).

Shiffman said deleveling across all subjects will make social studies even more heterogeneous because of class scheduling. He said the result will be better representation in WHISP classes of the whole student body.

“When the other departments delevel, our job will be easier. Last year, I had a section loaded with kids in Advanced Geometry. They were very studious, very committed, very anxious, which has its pluses and minuses. But the reality [was] they all wanted to get an A, or they wanted very good grades and were willing to work very hard to get them. But I don’t want that to be the dominant culture either,” Shiffman said. “The point of heterogeneity is some people are like that, and some people aren’t that worried about it.”

As the school considers greater deleveling, Shiffman said he wants to focus on deleveling in earlier grades of high school as opposed to later grades, which will allow students with different interests to pursue their individual passions.

“At some point, you do begin to specialize. But in 9th grade, and I would say even in 10th grade, I don’t want it to be leveled. I want to make it much more accessible and open,” Shiffman said. “And then in junior and senior year, you just do your thing.”

Share this:

Click to print (Opens in new window)Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

Pilot unleveled math programs

In the pilot deleveling programs in math prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which Paris said were largely successful based on overall positive feedback in exit interviews with students, Paris said the largest obstacles were connected to 9th graders already forming identities based on their levels.

“The biggest challenge that we faced was in the fact that it was a pilot, which underscores a reason why I think it’s imperative that we do this work. We did the pilot work in the spring, so students had already been in their levels for six months and at that point, students had cemented their identities; their mathematical identities were already very fixed,” Paris said. “There were some students who were so set that they were in a certain level and had a challenging time thinking outside of those parameters.”

Paris said he hopes to eliminate students’ tendencies of confining their mathematical identities to their level.

“We’re trying to flip that now and say, ‘You’re not an advanced student, you might be in Geometry Advanced, that’s the work you’re doing, or you might be in Geometry Honors, that’s the work you’re doing. It doesn’t mean you’re an honors Geometry student, those are different things,’” Paris said.

In the brief pilots, Paris said students already began to change how they thought about math and collaborate with other students.

“In working with other students who weren’t in their level classes, students really expanded the way they think about what a mathematician is, and so students who were in advanced saw that just because students weren’t in advanced, they could still do quality math work and be effective mathematicians. And even more so perhaps, students in college prep saw they could hang out with students in Geometry Advanced, and they could do the work and they could participate just as much as those students,” Paris said.

Due to the emphasis on collaborative learning in math classes, the pilot demonstrated the need to instruct students on working together inclusively and productively, Paris said.

“If we just throw kids in a group, and say, ‘Do this math problem,’ then the most vocal, strongest math student is going to dominate. That’s not going to help those students who perhaps need more time to do the problem,” Paris said.

In addition to considering classroom dynamics, Paris said a new program will possibly need to restructure student assessments, which the department learned about from the pilots.

“If we just give a traditional pencil-on-paper math test, those play into the strengths of students who currently are in our higher level courses and that’s not necessarily the only way to assess student understanding. Being smart in mathematics isn’t just being able to complete a series of ten problems in an hour, it is being able to communicate effectively about mathematics, to write effectively and to collaborate with your peers on mathematics,” Paris said. “As we build this program, we need to think about what we value as mathematicians, how we want our students to grow as mathematicians, and we need to match those values to the way we assess them.”

Students in Social Justice Leadership took a field trip to the Massachusetts Correctional Institution, a medium security prison alongside Project Youth, a program run by MCI-Norfolk.

From HBO’s “Oz” to Netflix’s “Orange is the New Black ” to Fox’s “Prison Break,” seemingly, cinematic depictions of prison culture are more omnipresent than ever, feeding viewers images of the “typical” inmate: dispassionate, belligerent and remorseless. Yet, several students have sought to redress the narrative, hoping to understand inmates beyond these supposedly hostile facades.

Students from the C and G-block sections of the Social Justice Leadership class visited the Massachusetts Correctional Institution at Norfolk (MCI-Norfolk), a medium security prison, on Thursday, Jan. 19 and Friday, Jan. 20, respectively. The trip, which takes place annually, was organized in accordance with Project Youth, a program run by MCI-Norfolk that allows inmates to share their experiences in prison with Massachusetts students.

History teacher Kate Leslie, who teaches Social Justice Leadership, said a strength of Project Youth’s is its ability to humanize inmates rather than exploit their stories to inhibit others from committing similar crimes.

“What makes Project Youth special is that it is not a ‘scared straight’ program in which the goal is to freak kids out and ensure that they never do drugs or drink and drive,” Leslie said. “[The program] is about helping students understand the humanity of incarcerated people, their decisions and the underlying factors, whether they be poverty or drug addiction or a history of sexual assault, that contributed to them breaking the law.”

Leslie said many of the stories told by the inmates correspond to the history and concepts explored in the Social Justice Leadership class.

“I teach my students about mass-incarceration and the ways in which the prison population has ballooned since the 1980s, especially due to the “Tough on Crime” movement and the policing of drug use. All of that tends to come up in the inmates’ stories,” Leslie said. “When they discuss why they are in prison, some of them talk about drug addiction, some talk about dealing [drugs] and others talk about receiving sentences that they felt were longer than they deserved.”

Following their visit to the prison, students were taken to the Brookline Teen Center, where they formed groups and reflected on the stories they heard. Senior Alex Levy said one story in particular felt powerfully resonant. It was told by an inmate named Ian, who recounted a night during which he operated a vehicle while heavily under the influence and killed a man.

“Ian grew up middle class and spent his summers vacationing in Cape Cod, like many students in Brookline,” Levy said. “He revealed his alcoholic tendencies but explained that he never thought of himself as an ‘alcoholic,’ as he drank beers every day, not hard liquor. He said something that especially stood out to me: ‘I thought of myself as a good drunk driver.’ Although this is counterintuitive to me, I hear many of my peers saying things like this quite frequently.”

Junior Malcolm Urena said the trip changed his perspective concerning inmates and their decisions.

“When I learned about the trip, I thought that the people in the prisons were there because they deserved it,” Urena said. “But after hearing their stories, it was hard to say that these people deserved to be in prison. They seemed to be normal people who had made a mistake that ruined their lives.”

Levy said the inmates she met were dissimilar from the stereotypical traits assigned to them in popular media.

“Hollywood tends to depict inmates as tattooed people in orange jumpsuits and shackles. It also portrays incarcerated people as cold and thick-skinned. These men, however, showed a great amount of remorse and were very vulnerable while telling their story,” Levy said. “One man even started tearing up as he recalled seeing his niece, whose life he hasn’t been able to be a part of while in prison.”

Leslie said hearing inmates’ stories highlighted the often overlooked structural flaws of the country’s criminal justice system.

“I’ve seen, in the past, that students have a sense that this country is failing to create a [criminal justice] system that rehabilitates. Sometimes, we say that the prison system is meant not only to punish people, but also to help them reform their lives and learn from their mistakes,” Leslie said. “However, when students hear these inmates talk about what prison is like, they don’t hear about that rehabilitative aspect. Instead, they might hear about how inmates cannot get time with a social worker or that they have not been able to address an underlying addiction.”

Junior Eli Traub said the trip’s immersive nature gave him knowledge and opportunities that he would not have otherwise achieved.

“I think this trip is so important because of the experience-based learning. I learned more in this trip than I did over my class’s entire prison unit, not from a lack of information during the unit, but from the value of experiencing things for myself,” Traub said. “No fact or statistic about the prison system can truly give you a grasp of what it’s actually like, and by listening to men who have spent years there, I was able to learn firsthand about the injustices and systemic issues in the prison system. Only through knowing this through experience will anyone be able to make meaningful change.”

Ravin Bhatia, Staff Writer|February 16, 2023