Ted Dintersmith and students hold a roundtable discussion surrounding topics like college and new innovations in education. Dintersmith, author and innovator, visited the high school on Sept. 20.

If you find yourself questioning the way Brookline’s education system is structured, you aren’t alone.

Ted Dintersmith, an advocate of innovation in education and author of What School Could Be, visited the high school on Sept. 20 during G-block. The visit was organized by the Brookline High School Innovation Fund, and it gave Dintersmith and 15 students an opportunity to discuss whether BHS is doing a good job for its students. Later that evening, Dintersmith led a second similar conversation, facilitated by WBUR’s Meghna Chakrabarti, in the Roberts-Dubbs Auditorium.

In discussing improvements needed in Brookline’s education system, Dintersmith and students focused specifically on the way students approached the college application process. In the conversation, Dintersmith and the students believed that the education system should do a better job of letting students explore options other than college and follow their interests more freely.

Dintersmith shared that an alternative to college – a gap year – can be a great idea, financially speaking.

listen “The gap year is for most kids, freshman year in college, where they spend 70,000 dollars to go to a bunch of parties and figure it out,” Dintersmith said. “I would say that most people think that a gap year is expensive; I’ve talked to kids that take a gap year who actually make money during the year, and for some reason people are just really reluctant to even think about that.”

According to junior Jasmine Benitich, with going to college as a norm, it can be difficult to approach alternatives such as a gap year.

“I grew up in a really strict household, so a gap year is never an option we have. It’s kind of a bridge to giving up,” Benitich said. “I don’t think I was ever taught in high school that a gap year is okay.”

Senior Ben Haber added that attending college is commonly what one has to do to succeed.

“There is the rare exception, like Mark Zuckerberg, who dropped out of college, but it is so rare and it’s so hard to ask students, ‘Why don’t you do something bolder, why don’t you do something different,’” Haber said. “I’d love to live in a world where we can all explore what we want to do, but we were born into a world where our education system has so much power.”

Dintersmith emphasized that if students are to go to college, it is important for them to know what they want to get out of their experience.

listen “It’s really easy to say, ‘I’m going to spend all college so that I can get the right job or graduate program. Then I’m going to spend those years so that I get into the right promotion,’” Dintersmith said. “You can do that for year after year after year and end up at my age and say, ‘I never did what I wanted to do.’”

Another area in which schools could improve, according to senior Eva Stanley, is encouraging students to follow their passions.

“Third grade onwards, we start to snap students into formulas, like ‘memorize this verb tense,’” Stanley said. “You get less and less flexibility up until the point in high school where you do have options to explore, but you become so afraid of how that’s going to impact your chances of getting into college, so you’re not going to take risks.”

Dintersmith believes that although college admissions tend to push towards the “routine and formulaic,” students should still remember to follow their interests instead of what everyone else is doing.

“Would you rather do the things you are passionate about and bring that to life in an essay or just keep checking off all those boxes?” Dintersmith said.

Sabrina Zhou

Yuen Ting Chow and Tree Demb

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Brookline High School Innovation Fund Presents:

What School Could Be – A Conversation About the Intersection of Education and Innovation with

Author and Innovation Expert Ted Dintersmith

WBUR’s Meghna Chakrabarti to Moderate this Free Community Event

September 20, 2018, 7:00-9:00 pm

BROOKLINE, Mass., August 9, 2018 – Brookline High School (BHS) Innovation Fund today announced it will host a conversation with innovation expert and former venture capitalist Ted Dintersmith, author of the new book, What School Could Be: Insights and Inspiration from Teachers Across America. The book offers an inspiring account of teachers in ordinary circumstances doing extraordinary things, showing what leads to powerful learning in classrooms, and how to empower teachers to make it happen. Moderated by WBUR’s Meghna Chakrabarti, the thought-provoking conversation will delve into how teachers can change the education system in creative, compelling and practical ways to positively impact students and better prepare them to succeed in the innovation economy and serve as responsible, contributing citizens.

The event, which is free and open to the public, will be held in Brookline High School’s auditorium (115 Greenough Street in Brookline, Mass.) on Thursday, September 20, 2018, at 7:00-9:00 p.m. Doors will open at 6:30 p.m. A reception will immediately follow the program. To register for the event, please visit here.

“I am incredibly excited for Ted Dintersmith to visit Brookline High School this September,” said Anthony Meyer, headmaster of Brookline High School. “As we celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the Innovation Fund, it makes sense to pause and push ourselves to think about the purposes of school, and how we can better develop students’ skills, agency, and knowledge that is both deep and retained. Ted Dintersmith’s What School Could Be builds on the most sacred relationship in schools: student and teacher. He shines the light on deep, meaningful learning that helps prepare young people for continued education and, more importantly, the broader world in which we live.”

Published in April 2018, What School Could Be captures the common elements of the powerful learning experiences that teachers across the U.S. are creating in their classrooms, and the ways leaders are changing schools at scale by establishing the conditions that let teachers and students thrive. During the 2015-2016 school year, Mr. Dintersmith took an unprecedented trip across America, traveling to all 50 states and visiting approximately 200 schools. As he traveled, he met innovative teachers all across the country — teachers doing extraordinary things in ordinary settings, creating innovative classrooms where children learn deeply and joyously. Each day, these students are engaged and inspired by their teachers, who in turn help children develop purpose, agency, essential skill sets and mind-sets, and deep knowledge. The insights of these teachers offer a vision of what school could be, and a model for how to help schools achieve it. The event is presented by the Brookline High School Innovation Fund, an incubator for new ideas that fosters success for all students by supporting academic innovation at BHS. Founded in 1998 as the 21st Century Fund, the Innovation Fund’s mission is to empower the BHS faculty and community by fostering a culture of innovation and supporting the development of new ideas and initiatives that will enable students to thrive in the new economy.

“Bringing Ted Dintersmith to Brookline is yet another example of the commitment the Innovation Fund has to the Brookline High School’s students and teachers,” said Andrew Bott, superintendent of the Public Schools of Brookline. “Year in and year out, the Fund benefits BHS students by helping to unleash the innovation and creativity within our teachers in a way that has long lasting impact.”

The BHS Innovation Fund invests in new courses, programs, forums and research that help administrators and faculty continue to deliver excellence in an evolving world. Working with BHS faculty and Town of Brookline administration, the Innovation Fund supports the design and implementation of forward-thinking ideas introduced by BHS faculty through a formal grant proposal process. Grants are vetted by both BHS administrators and the Innovation Funds’ board of directors. After a three-year testing and evaluation period, successful investments in new courses may become permanently funded by the Town of Brookline.

About Ted Dintersmith

Ted Dintersmith, PhD, is a change agent, philanthropist, author and documentary film producer, focused on issues at the intersection of education, innovation and democracy. In addition to authoring What School Could Be, he is the co-author of Most Likely to Succeed: Preparing Our Kids for an Innovation Age. He funded and produced the documentary film Most Likely to Succeed, which received critical acclaim and premiered at numerous film festivals, including the Sundance Film Festival. He was also the executive producer of The Hunting Ground, a film about sexual assault on college campuses. From 1996-2015, Mr. Dintersmith served as general partner of Charles River Venture Partners in Cambridge, Mass. In 2012, he was appointed by President Barack Obama to represent the US at the UN General Assembly, where he focused on global education issues, collaborating with UNICEF, the UN Foundation, and the Secretary General’s Office of the UN. He received his PhD in Engineering from Stanford University.

Event Details

What: BHS Innovation Fund Presents: What School Could Be: A Conversation About the Intersection of Education and Innovation with Author and Innovation Expert Ted Dintersmith

When: Thursday, September 20, 2018, at 7:00-9:00 p.m. (Doors open at 6:30 pm)

Where: Brookline High School Auditorium, 115 Greenough Street, Brookline, MA

Reception to immediately follow in the BHS Atrium

Transportation: MBTA: BHS is located at the Brookline Hills MBTA subway stop on the Green Line “D”

Parking: On street parking is available

Admission: Free and open to the public

Registration: Registration is recommended. Click here.

###

Media Contacts:

Michele Rozen: 617-953-2214

Mara Littman: 617-304-9488

Email: bhsinnovationfund@psbma.org

Juniors Josh and Kayton Rotenberg were participants in the high school’s trip to Berlin last October for the World Health Summit. This was just one of many trips the Global Leadership program runs.

Last October, sophomore Zeb Edros found himself surrounded by other people who truly cared about health issues in the world. The catch? He, along with other students from the high school, were the only non-professionals at this conference. Oh, and they were in Berlin.

Every year, students have the opportunity to travel to places such as Amsterdam, Portugal, Nicaragua, Tanzania and Berlin, some in the Global Leadership class, some not, but they all have a shared an interest in world health and learning.

The trips serve as a non-traditional approach for the students to learn and gain experience in a different environment.

According to social studies teacher Ben Kahrl, who teaches the Global Leadership class, the trips function to give the students insight on real situations.

“The trips have two purposes. One is for students to work with and get mentoring from adults who are seeking to solve real-world complex problems. The other is so that they can see these real-world complex problems,” Kahrl said.

According to Edros, who travelled to Berlin for the World Health Summit this past October, the conference was a unique experience for him.

“I think the fact that we were the only students at a professional conference meant that everybody talked to us as if we too were their equals, which let us understand not just more about their fields, but just how to interact with these people in general,” Erdos said. “They answered our questions. They gave us advice on our futures which is really helpful.”

Kahrl believes that the information and skills that the students learn on trips like these will help improve their future and their range of possibilities.

“They {now} have confidence. They can enter the adult world and have conversations with professionals rather than being on the sidelines,” Kahrl said. “Students get exposed to possible careers that they wouldn’t otherwise, simply because they meet people who do things they’ve never heard of.”

According to Kahrl, many of the students who go on Global Leadership trips are in the Global Leadership Class. Sophomore and Global Leadership student Jack Heuberger said that the students do a lot of work pertaining to many different aspects of global problem solving.

“You also learn about situations happening in other countries, such as the Libya slave crisis, and you have to think about ways to possibly solve those problems,” Heuberger said. “It’s about a lot of learning about how the world works and government and how other governments work together, and it’s a lot of critical thinking and collaboration.”

Kahrl said that he hopes to expand the program and give the opportunity of traveling and learning to many more students in the future.

“My goal is that all students, regardless of their socioeconomic background, have a chance to get mentoring from people around the world, and to have an opportunity to travel to places where these challenges are real and immediate” Kahrl said.

Contributed by Kayton Rotenberg

Dan Friedman, Staff Writer

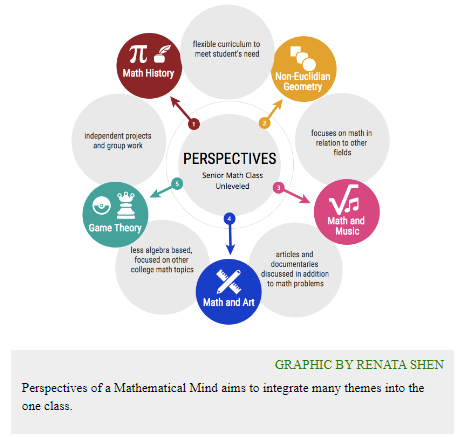

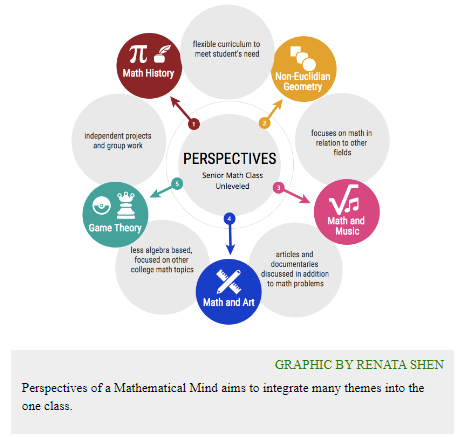

Perspectives of a Mathematical Mind aims to integrate many themes into the one class.

By the end of high school, an average math student can write a geometric proof, solve a quadratic equation and maybe even calculate a derivative. Give the student a traditional math textbook and a sheet of lined paper, and they’ll know exactly what to do — but ask that same student about non-euclidean geometry, game theory, the history of math, or real-world applications of operations and formulas, and you will likely receive a blank stare.

That is, unless you ask students from a senior math class, Perspectives of a Mathematical Mind, which introduces non-algebraic college math and connects concepts with other disciplines such as art, music and history. Through taking the class, students incorporate their own interests with math projects, which deepens their engagement and understanding of the material.

Math teachers Betty Strong and Grace Wang brainstormed the idea for the class after observing a lack of student interest in other algebra-based math classes.

“We would sit around and just be like, ‘it’s such a bummer that students don’t get a chance to see all of this really cool stuff about math,’” Strong said.“There’s so much more to math that kids don’t see.”

After submitting a proposal to the Innovation Fund, then called the Twenty First Century Fund, Strong and Wang received a grant to run the class for three years. After this trial period, the funding for the course was incorporated into the school’s math department budget. The class now covers topics such as tessellations, fractals, art, music and more. Although the class includes some mathematical calculations, the bulk of the class is spent completing other activities.

“We do a lot of group work and presenting, we watch videos, we read articles, we do a lot of discussions, we do a lot more in-depth math investigations,” Strong said.

Although she was already on the advanced math track freshman through junior year, senior Damani Gopal chose to take Perspectives this year, in addition to Advanced Placement calculus.

“I want to study computer science when I’m in college, so obviously the STEM fields are really big in my life,” Gopal said. “Taking a second math was a big benefit.”

Senior Noah Sesling chose to take the class after a presentation given to his Trigonometry and Analysis class junior year. Prior to taking the class, he had struggled to connect class material to his daily life.

“I liked the idea of taking a math class that actually could teach me things that I could apply to the real world,” Sesling said.

For Gopal, learning about other aspects of math has allowed her to extend her existing knowledge of STEM. She particularly enjoyed a unit on game theory, a field of study that is heavily rooted in human psychology.

“It’s the analysis of how two or more parties choose to play a certain game, so it can be like applied to fights like wars, or it can be applied to games,” Gopal said. “There’s a lot of connection to computer science to that. I’ve done game theory independently, so it was lot of fun to do it in school.”

During a unit on math and art, Gopal was able to apply her interest in coding to an end of unit project.

“I made a computer program that depicted tessellations and fractals, so involving coding with math,” Gopal said.

Sesling has incorporated his interest in music with math class. At the high school, Sesling participates in both Camerata choir and the a capella group, Testostatones. For one of his projects, Sesling studied twelve-tone serialism, a form of music composition.

“It basically uses numbers to create melodies,” Sesling said. “I found that really interesting, the way that Perspectives taught me and gave me the resources, and opportunities and open-endedness to actually explore how math and music come together.”

According to Strong, a unique aspect of the class is that it is non-leveled, allowing students who normally don’t interact an opportunity to learn together.

“There’s not a lot of prerequisite knowledge that students need, so we take kids from the college prep level all the way up to the advanced level,” Strong said, “the course is based on each student reaching their own level of mastery, so there’s a lot of individualization.”

For Sesling, taking the class has helped him recognize the significance of mathematical concepts.

“[Before Perspectives] I spent a lot of time memorizing and just trying to think of concepts that didn’t have a meaning to me. This idea of just 1+1=2,” Sesling said. “But with perspectives, it’s a lot more [of] much larger concepts rather than simple small ideas or equations. It’s not like anything you have to memorize, it’s just concepts, like how math would relate to everyday experiences or other forms of art.”

Renata Shen, Staff Writer

The Brookline High School Innovation Fund is proud to announce national recognition in C-SPAN’s StudentCam 2018 Video Documentary Competition for BHS students Chloe Janes, Bryan Zhu, and Romy Meehan for their film,

Under Siege. Responding to the competition theme, “The Constitution and You,” these seniors won Third Prize for a documentary they made in BHS’

Film as History/History as Film elective. Launched by the BHS Innovation Fund in the 2016-2017 school year, this is a year-long course, co-taught by Mark Wheeler (Social Studies) and Thato Mwosa (Visual Arts) that explores how history is documented in written form and documentary film, helping students maneuver both word and image to be truly effective communicators in the 21st century.

Under Siege looks at the First Amendment and how the current media climate under the Trump Presidency affects how journalists do their work.

The Brookline High School Innovation Fund catalyzes innovation at BHS and energizes our faculty. The Fund’s goal is to invest in courses, programs, forums and research that help administrators and faculty deliver excellence in an evolving world. After a three-year testing and evaluation period, successful investments in new courses become permanently funded by the town of Brookline. We serve as venture capital for public education, thanks to direct financial support from parents and the broader Brookline community.

See the award winning video here: https://www.viddler.com/v/d4a952b8

Photo L-R: Students Chloe Janes, Romy Meehan, Bryan Zhu

Students posed for a group photo during their time in Berlin. They attended the World Health Summit conference in October.

All teenagers know the anxiety that can come with sitting down next to strangers at lunch. But that feeling of anxiety becomes a lot worse when you are in a foreign country trying to put your plate down next to a full-fledged medical professional.

For 17 students, this was a reality for a week in October. Being given the chance to attend the World Health Summit in Berlin gave these students new experiences and knowledge about global health, global health security, cancer in Africa and other skills.

To be accepted to be a part of the trip, students filled out an application last spring, consisting of multiple essay questions. The 17 students, along with three teacher chaperones, left on Oct. 13.

Junior Katie Rotenberg, one of the students who attended the trip, said that since students are not medical health professionals, the purpose of the trip was to expand their experience in the fields discussed, including medical and scientific fields.

“We went to Berlin for the World Health Summit, which was a gathering of international scientists, doctors, global health leaders, politicians and all kinds of different things, so it was a really great mix of science and global policy,” Rotenberg said.

Social studies teacher Ben Kahrl, who teaches the Global Leadership class, said that one benefit the trip offers for him is the perspective on international health and the views of other countries.

“Boston has huge amounts of medical stuff; it’s world class. But when you go to Germany or Montreal or Portugal, you meet people from all over the world and see how they look at the world differently than us,” Kahrl said.

This trip allowed students to see and meet many professional doctors and politicians who had influence over the medical community. Rotenberg said they met the uppermost people of the field.

According to senior Jerry Chen, being the youngest members of the conference provided the group with unique opportunities.

“We were the only high school students there and we were able to meet so many professionals and famous people you can normally only see on TV or social media,” Chen said.

The conference hall was arranged as a rotunda, with an auditorium in the middle, surrounded by a circular hallway. Keynote speakers held talks in the middle, while conference rooms around the outside of the hallway were for smaller conferences or workshops.

Rotenberg said her favorite speech was made by the princess of Jordan. Since she is a princess and the head of multiple cancer organizations, she uses her authority to administrate others helping find cures, Rotenberg said.

“She was just in the audience two rows behind us, and she gets up and makes this very, very passionate speech about how you can’t begin to have all this high tech stuff in communities until you first have the structure there,” Rotenberg said. “You can’t go and give everyone laptops when they don’t have running water and basic things like that.”

Chen said he thought the most inspiring speaker was the host of a talk concerning cancer in Africa. This speaker talked about his experience and brought his message to the audience.

“He decided to study abroad in England for five years to learn skills to treat cancer, but it was very sad when he came back and realized they wouldn’t have any clinics or technology available in Africa to actually use these skills,” Chen said. “That was very powerful.”

Chen said he didn’t realize how many obstacles there are within public health, including political and technological challenges.

“Before I went on the trip, I wasn’t super interested in public health, but afterward, I felt like it really was our job to make sure that people in the world have access to proper medical care and treatment to their diseases,” Chen said.

Rotenberg said that being part of the conference could be intimidating. Chen agreed that meeting and talking with the professionals at the conference was difficult, especially since they were strangers, but it got easier throughout the week.

“You had to really just go out there and be aggressive. During lunch, put your plate down in front of some scientist and be like, ‘I’m going to sit here now; let’s talk,’” Rotenberg said. “If you didn’t do that, I think you really missed out on a lot of good opportunities.”

The conference helped provide students with the unique experience of learning about possible future career paths. Rotenberg said she probably wants to go into medicine. Chen said he wants to go into medical engineering to research new treatments for Down syndrome.

Kahrl said that being in an environment with professionals who have pursued these dreams for themselves offered a good example for students on how many career opportunities now exist.

“In terms of exploring careers and the breadth of careers, rather than just saying ‘I’m going to be a nurse or a doctor,’ there are all sorts of roles in public health that people can get into,” Kahrl said.

CONTRIBUTED BY JERRY CHEN

Madison Sklaver, Staff Writer

At BHS, there are many different cross cultural trips. The Spanish classes go to Spain and Mexico, Latin to Italy, French to France and the Chinese students on the Chinese Exchange program, just to name a few.

Global Leadership is a full-year elective offered at the high school beginning in 10th grade. Students in the class have the opportunity to go on many trips including to Berlin for the Women’s Health Summit, Copenhagen for the Women Deliver Conference, Montreal for the World Health Summit, London for the Global Health Film Festival and many others. This past summer, a group of students went on a cultural exchange trip to Zanzibar, Tanzania.

Teachers Ben Kahrl, Joanne Burke-Hunter, Stephanie Hunt and Rochelle Joan Mains accompanied juniors Rebecca Downes, Bella Ghafour, Henry Bulkeley, Brian Bechler, Ben Caplan and Hector Cabrera, and seniors Maansi Patel and Hugh McKenzie.

A lot of work goes into planning a trip like this, and according to history teacher and leader of the trip Ben Kahrl, many plans changed due to unforeseen circumstances arising.

“We were going to go to Nicaragua and they had Zika, so we couldn’t go. I had an application to Ethiopia, and riots broke out against the government, so we pulled that application,” he said. “So, trying to find a place that is interesting, different and safe does have some challenges.”

Kahrl said he selected Zanzibar, Tanzania as the destination for the trip because it is a safe and interesting country to visit, and having been there before, he had contacts there.

According to senior Hugh McKenzie, the purpose of the trip was cultural exchange and learning about global health, and also understanding what living in a predominantly Muslim society is like.

“We played soccer with some of the women’s soccer teams because in a Muslim country, it is difficult to have that right. We visited NGO [Non-governmental organization] projects in Tanzania and met with rural locals who are a lot poorer than the people in the main town,” McKenzie said.

Junior Bella Ghafour said that while in Tanzania, they went to a lot of schools and interacted with the students who went there, shadowing classes and participating in different activities with them.

“We went to a bunch of different schools,” she said. “Some were pretty, higher class, and you could see better schools, better desks, better everything, and then there were some that you could see were a lot less fortunate in their resources.”

Kahrl talked about their visit to one of the schools specifically, which was a Muslim school.

“It’s really equivalent to our Catholic schools,” Kahrl said. “I think that when people think Islamic, they think ‘oh my god, madrasa,’ and that means brainwashing, though we would not say the same thing if a kid were sent to a Catholic school here.”

McKenzie spoke about their experiences going to the SOS School and interacting with the students there.

“The SOS School is a school for orphans. It’s probably the best school in Zanzibar and it’s very selective. What we did was we met with the high school students, and we really bonded with them. We understood their lifestyle a little better, and they understood our lifestyle. There was a lot of cultural exchange. Definitely exchange, not just understanding their culture but understanding each other’s.”

For McKenzie, meeting with the SOS high schoolers was the most meaningful part of the trip.

“They live a different lifestyle than us, and they definitely have a different perspective of the world, and things like marriage and sex, which are a lot different in that country,” he said. “The way they see things is very construed towards a Muslim view in an urban setting, and seeing them was so meaningful because it made me reflect on our society and how we see things.”

For Ghafour, the most meaningful part of the trip was visiting the Big Tree school.

“It was one room,” she said. “I guess you couldn’t even call it a room, just a really beat up house that was for 25 kindergarteners and one teacher for the whole school and you could tell that they didn’t have many resources. When we came, we were playing with them, doing the parachute, and the teacher was just so, so happy, and you could see how just small things made them incredibly happy, and it just makes you think about your own life.”

For Kahrl, one of the most powerful moments was when they visited a different Muslim school that he described as being more like religious after school program.

“We heard about the five pillars and then a young man, maybe 12, 14 years old stood up and sang the call to prayer, which I find tremendously powerful even though I’m not Muslim and I don’t understand a word of it,” he said. “I think it is incredibly beautiful, and he sang it through with this incredibly gorgeous voice…At the end, all of the students sang a song, and again I didn’t understand any of it, but it had parts weaving through and it was one of the most beautiful songs I’ve ever heard in my life, and to have Americans see the part of Islam that we don’t see in the news, but is people visiting with people, and both groups really loving it.”

Kahrl hopes to keep this as an ongoing exchange, currently planning trips in February and July.

Ben Mandl, Opinions Multimedia Managing Editor

How does a writing teacher return to the “beginner’s mind” of students, and how does doing so influence his teaching practice? Ben Berman shares how the frustrations he experienced and the lessons he learned when he tried to write a screenplay changed the way he approaches teaching writing to his high school students.

Despite the fact that I don’t own a TV, don’t subscribe to Netflix, haven’t been to a movie theater in years, and wouldn’t know a slug line if it slugged me in the face, I decided to add a screenplay unit to my creative writing class this year.

To prepare for this, I applied for a grant from the Brookline, Massachusetts High School’s BHS Innovation Fund to spend my summer working on my own original screenplay. Not only would this teach me a little something about the genre, I thought, but if I happened to pen a big hit I just might never have to cover lunch duty again.

As a poet, I had very little experience writing dialogue or plotting stories into three acts. But returning to beginner’s mind offered me many insights into the challenges that my students—who are often writing creatively for the first time—tend to face.

I have tried to describe, here, the messy evolution of my screenplay and how it’s changed my approach to teaching creative writing.

Writing the Screenplay

DRAFT 1: Transformations

My first idea involved a character that feels lost in the modern world until he starts helping out at a funeral home. I was particularly interested in dramatizing an inner transformation through motifs and spent a week meticulously plotting the story out and storyboarding some of the scenes.

But when I actually started to write the screenplay, I ran into the same problem that my students often face—my characters weren’t interested in doing what I wanted them to do. I’d planned their lives before I’d taken the time to get to know them, and I soon realized that I would need to start over with a new premise and new process.

DRAFT 2: Are We Here Yet?

A few days later, I ran into a former student who had recently graduated from college and was struggling to figure out whether to accept a job offer or spend the summer travelling abroad. She asked me for my advice. I asked her if she wanted to be the main character in my screenplay.

I started wondering what would happen if people didn’t actually have to make big life choices—what if my character could implant part of her soul into a pod and then send that pod abroad while she started her career? Would this solve my character’s problem, I wondered, or simply create new ones?

After working with this sci-fi premise for a little over a week and discussing it with everyone I knew, a screenwriter friend asked if I understood the whole budget aspect of films. What do you mean? I asked. If you set ten minutes of your film abroad, he told me, you add $100,000 to your budget.

And I realized that I was still writing with the freedom of a poet, rather than attending to the realities of this new genre.

DRAFT 3: The Fad of the Land

The next day, I was at the farmer’s market with my daughters when I saw a sign for Paleo Cookies. Paleo cookies? I thought. What Paleolithic ancestor ate vegan chocolate chip cookies sweetened with agave nectar?

I decided to start over entirely and write a comedy about two rival groups—the Paleos and the Kaleos—at a farmer’s market.

I knew right away that this was a dumb idea—that I was writing a skit and not a feature-length film—but sometimes pursuing dumb ideas is an essential part of the creative process. It pressures us into a minor existential crisis, forces us to step back and reconsider our connection to our work.

And as I was thinking about why people would want to return to the traditional diets of our ancestors, I started contemplating my own relationship to the modern world, how the experiences that have felt most transformative to me—serving as a Peace Corps Volunteer and becoming a father—both involved a return to simpler ways of living.

DRAFT 4: Vicarious 1

All of a sudden, I started to see some connections and patterns in my drafts and realized that what I really wanted to explore was this: In what ways do the modern technological advances in this world help us feel more fulfilled? In what ways do they only exacerbate our loneliness?

I decided, then, to return to my previous sci-fi premise. My next draft was called Vicarious and was about a woman trying to save her family’s pod service company from being sold to a hedonistic rival group.

This draft seemed to be going quite swimmingly—I felt deeply connected to the existential anxiety of my characters and had written half the screenplay when I realized that while I’d surrounded my protagonist with all sorts of interesting, quirky and troubled characters, she was primarily a witness to the world around her—no struggles, desires or conflicts—and therefore no potential for an interesting arc.

I was disappointed that I was going to have to start over again—but I knew, too, that a heightened awareness of problems in a creative work is always a healthy sign.

DRAFT 5: Vicarious 2

So after three weeks of getting to know my main character, I decided to get rid of her. I kept the sci-fi premise but chose one of my minor characters to be my new protagonist—someone who uses her pod (now called Vikes) to avoid and escape—and someone with the desire to change, as well. Finally, I had both a plot and main character with potential, and the first twenty pages of the screenplay flew out of me in less than a week.

The only problem, now, was that summer was over.

Some Takeaways

I went into this project thinking that it would teach me the craft behind screenwriting. And in many ways it did. But the real question that emerged for me was this: How do we help students embrace the incredibly messy process of creative work?

You Say Revise, I Say Revive

It took me five different story treatments and well over 200 pages of writing to net the first act of a screenplay. Yet each attempt was a better failure than the previous one. And that’s not just because I’m a really bad screenwriter—every poem I’ve ever published has a hundred pages of failed drafts behind it.

And yet something that felt like such a natural part of the process to me—starting over—was something that my students always seemed to resist.

One strategy that I tried out this year was having my students write vision statements (sometimes called What-the-Hell-Am-I-Doing Statements) after they completed their first drafts.

One student, for example, had written a ten-page screenplay about the fallout between three friends after two of them begin dating. In her first draft, she followed the arc of the character that became the third wheel. But in her vision statement, her story was exploring what it means to follow your heart even if it hurts someone else.

When we sat down to conference and recognized this disconnect, it was like a split-screen scene out of Annie Hall.

Now you just have to switch main characters and rewrite the story, I said.

Now I have to switch main characters and rewrite the story??!! she said.

Once she accepted this, she produced a much more realized draft. And I realized how important it is to build enough time into my units for deep revisions, to teach students the difference between finding material and shaping material, and to convince them that starting over is not a step backward but a step forward in a better direction.

Breaking Those Seas Frozen Inside Our Soul

But if I was going to ask my students to commit to deep revisions, I needed to help them think of their work, as Frost wrote, as (a screen)play for mortal stakes.

Another student, for example, turned in a first draft that was fifteen pages long and followed eleven different characters. When we sat down to conference, I suggested that she, umm, perhaps, choose one or two characters to focus on.

I can’t, she said.

Why not? I asked.

I can’t decide which one, she said.

And then suddenly she was on the verge of tears, talking about the college process and having to decide between theater and field hockey, and these two very different boys that she kinda liked, and how she never really knows what to do, and how her plot (or total lack thereof) was just one more example of her inability to ever make a decision about anything.

After depleting our class’ PTO-sponsored box of tissues, we stepped back and realized that maybe what she really needed to do was transfer her own personal struggles onto her characters and let them deal.

She wrote twenty brilliant new pages over the weekend, following the story of a young actor struggling to decide whether to accept a role in a movie in which he’d have to appear nude.

When we first sat down to conference, I had thought she needed help understanding the art of rising action; it turned out that she just needed to find a theme that she cared deeply about.

Putting My Grades Where My Mouth Is

If I wanted my students to embrace the messiness of the creative process, I needed to shift how I was grading them and put much more weight on process, learning, and habits of mind.

I had one student, for example, who decided to adapt his favorite sci-fi book into a screenplay. His final product was pretty good, but it wasn’t until I read his reflection—where he documented the struggles of his process—that I was truly able to see just how much he had learned. Here is a paragraph from his reflection:

I began with the main events that I knew I wanted to transfer from the book to my screenplay, and wrote them down on a timeline. I then got more and more specific, choosing what events I wanted to translate, and ordering them in a way that both made sense and followed the three-act structure that movies so often do (in a book, for example, climaxes are not built up to as dramatically as in a movie). This turned out to spawn a sort of liar’s paradox, because whether a specific event could be included often depended on if there was a place for it, but where an event was to go often depended on whether another event could be included. In addition, the interwoven subplots and their subtle interactions with the main plot made the process somewhat like that of putting together a jigsaw puzzle made of shape-shifting pieces.

In creative projects, our learning is often inversely related to our success. My best students weren’t necessarily the ones who were producing the most polished pieces—they were the ones coming away from their experiences with the most nuanced understanding of the challenges they had faced.

Conclusion

Slogging through my own screenplay made me realize that while I was offering students many opportunities to be creative, I wasn’t really teaching them how to be creative. I was showing them what good writing (the noun) looked like, but I wasn’t teaching them what good writing (the verb) looked like.

Even in my creative writing classes, I tended to offer students neat packages of learning with a focus on product over process: here is some content, here are some skills, here is an assignment that will measure your learning.

But the creative process looks more like this: here is a setback, here is a minor epiphany in middle of the night, here is where you need to start over.

Just the other day, I received the following email from one of my students on the verge of completing her first draft of a twenty-page screenplay.

I just woke up in the middle of the night (it’s 3:25 am) and realized I’m not really passionate about my story. I think it strayed way too far from what I originally wanted to accomplish because looking back that goal was a little too big and overwhelming. So now it’s turned into something completely different that I barely have any personal connection to. So I’m kind of freaking out here. I want to rewrite it but I’m worried it’s too late. What should I do? Ahhhh!!!

And as messed up as this sounds, I almost cried tears of joy.

Teaching craft is essential. But if I want my students to think of writing as a lifelong apprenticeship, what I really need is to teach them to embrace the spirit of what Beckett meant when he said, Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.

Ben Berman began his teaching career as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Zimbabwe. He then spent eight years teaching in the Boston schools and has spent the past eight years at Brookline High School in Massachusetts, where he teaches creative writing and helps run the Capstone program. His first book, Strange Borderlands, (Able Muse Press, 2013) won the Peace Corps Award for Best Book of Poetry, was a finalist for the Massachusetts Book Awards, and received a starred review from Publishers Weekly. His new collection, Figuring in the Figure, is recently out from Able Muse Press. Berman is the poetry editor at Solstice Literary Magazine and lives in the Boston area with his wife and daughters.